Why is Mt Noorat here?

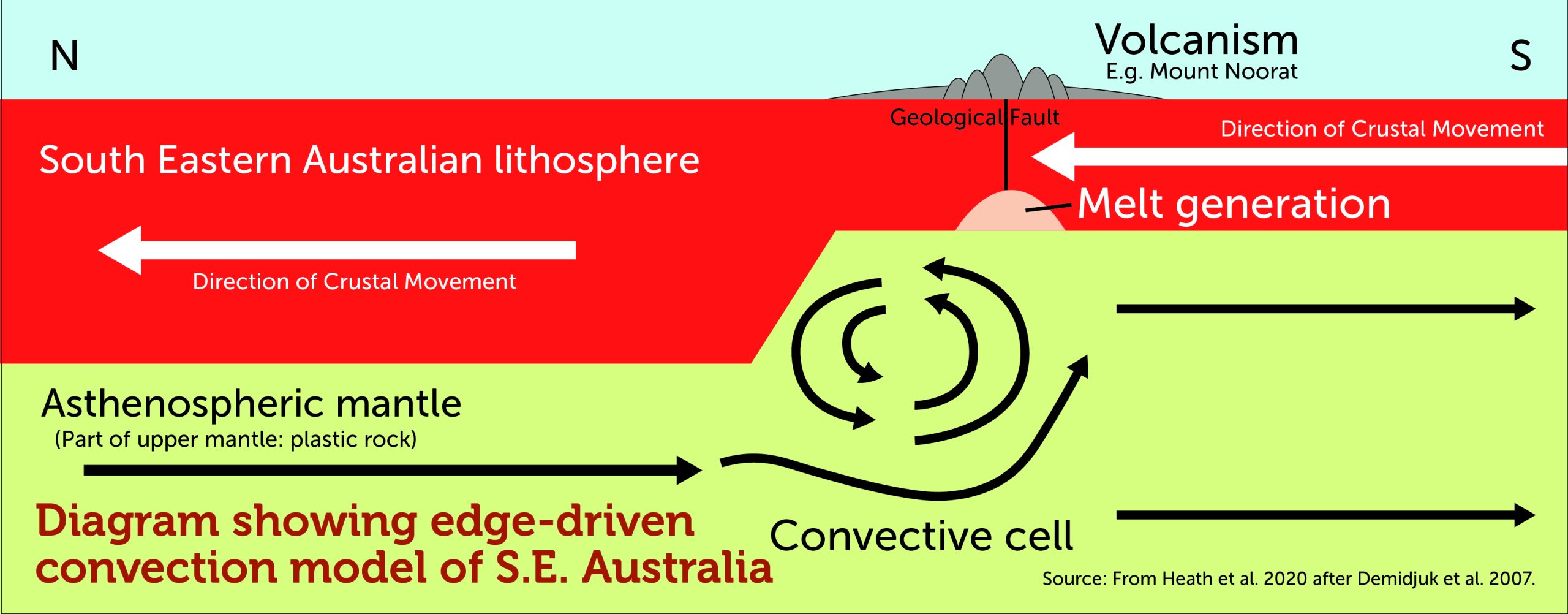

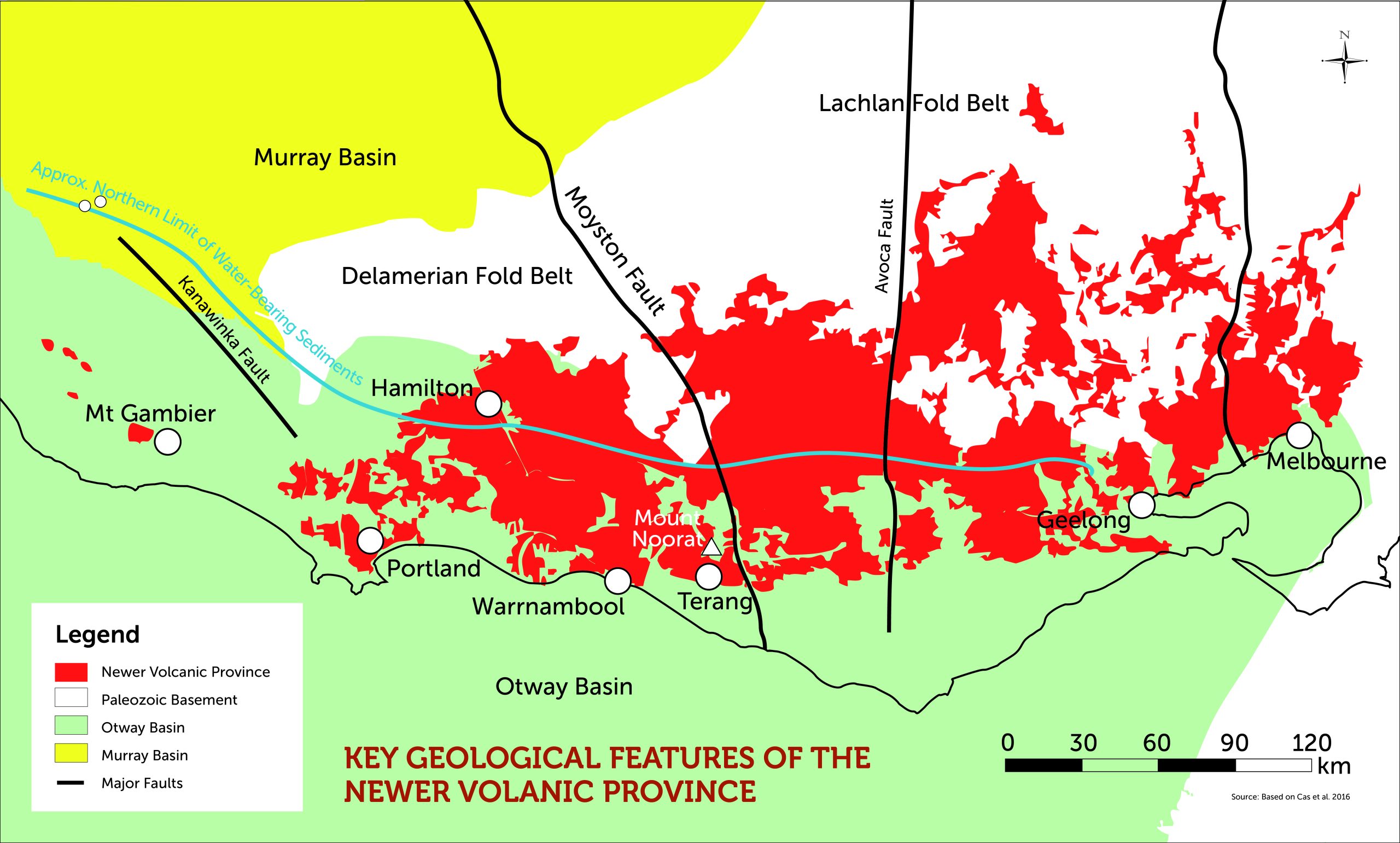

You have perhaps noticed that the Newer Volcanics Province occurs within the Australian tectonic plate. Most volcanism around the world occurs near the edge of tectonic plates, so that volcanic products like those in the Newer Volcanics Province warrant a particular name – intraplate volcanics. Mt Noorat is an example of intraplate volcanics. In the case of the Newer Volcanics Province, it appears that intraplate volcanism arises primarily from the melting of deep-seated rocks beneath south-eastern Australia as a response to two main factors. First, abrupt increases in the thickness of the lithosphere (Earth’s crust plus upper mantle) here favours the development of convection cells of hot, malleable rock in the mantle just below the lithosphere (see visual below)

Secondly, compression at the New Zealand margin of the Australian plate causes buckling of the plate beneath south-eastern Australia. Buckling can create faults, or lines of weakness, through the crust and also eases the pressure on the mantle and results in melting of a portion of the rock there. The resultant magma makes its way to the surface along ancient faults which help to localise eruptions.

In the case of Mt Noorat, it sits above the greatest discontinuity (fault line) in Victoria’s geology. This is called the Moyston Fault, exposed at Moyston (just east of the Grampians) and buried beneath the Otway Basin in the Noorat area. (see visual below).

This and other major buried faults act as a kind of plumbing system that directs magma through the crust to the surface.

Large volumes of basaltic lava had therefore spread across western Victoria’s plains well before the eruptions occurred that formed the Noorat volcanic complex. The average thickness of the lava across the VVP is about 60 meters but the thickness can vary enormously depending on location. Other materials to come from volcanic activity in the NVP include a range of different sized fragments ejected during volcanic eruptions. These fragments are collectively called tephra.

How was Mt Noorat formed?

Mt Noorat as we see it today is not just a simple scoria cone volcanic formation. It is in fact part of a volcanic complex developed during a series of eruptions over a period of months or even a few years with no major time breaks. This is considered a short period of time.

Looking on site today, while Mt Noorat is the most obvious landform in the Noorat complex, there are several other landforms present including low mounds, small craters, tuff rings and lava flows.

Early features in the formation of the complex, especially the tuff rings, are obscured from view, being covered by later eruptions and materials.

The Noorat complex developed in 3 stages, as outlined below:

STAGE 1 - MAAR CRATERS and TUFF RINGS

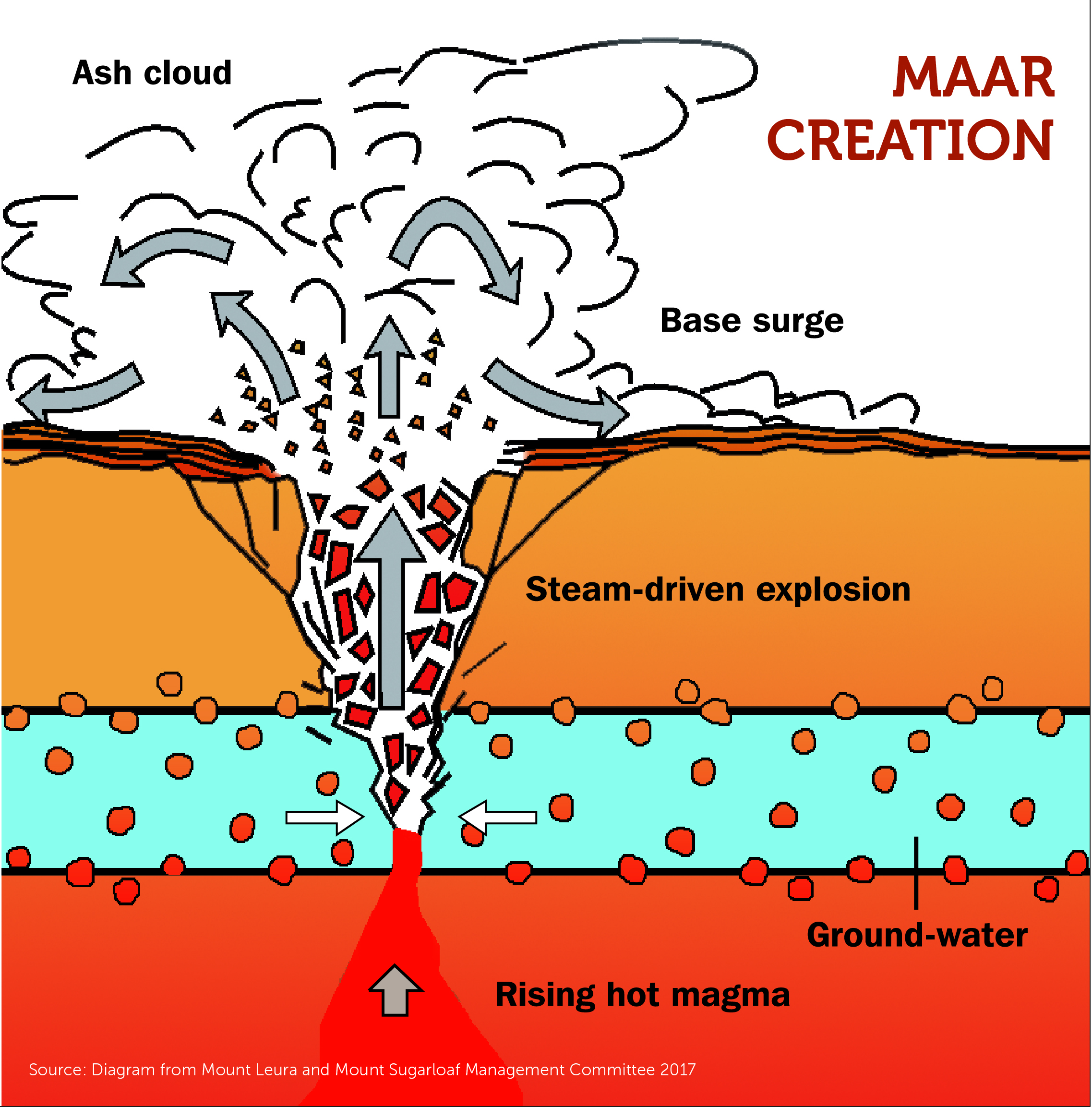

The formation of the maars and tuff rings represents the first stage of the Noorat volcanic complex. This occurred when a violent interaction (explosion) took place when rising magma (10000C) met groundwater (1000C) in the underlying rock aquifers turning it instantly from liquid to gas. (see visual to right) It is this enormous increase in pressure that blows out a crater - known as a maar, This explosive excavation of rocks, at and below the former land surface, along with magma derived fragments from the eruption, build up in layers at the edges of a maar to form a low tuff ring - mainly of ash sized fragments

- Layers of Tuff

Careful mapping at Noorat by experts has shown that successive eruptions in fact created two intersecting maar craters. The southern tuff ring is roughly circular and about 2 km in diameter while the northern one is about 800 m across and of uncertain shape.

The later stages of volcanic activity have buried all of the maars, so it requires one’s imagination to remove Mt Noorat and to picture the maars beneath it. An impression of one of the tuff rings can be gained by following the road from Noorat toward the north on the western flank of Mt Noorat, where the rise is due to the presence of the tuff ring. Even here, the tuff ring is covered by black scoria from a later eruption, as Molan’s quarry shows.

Unlike many of the other maars on the VVP eg Lake Keilambete and Lake Bullen Merri, the Noorat maar did not fill with water as the follow-up volcanic activity ensured that the crater bottom was above the level of the local water table.

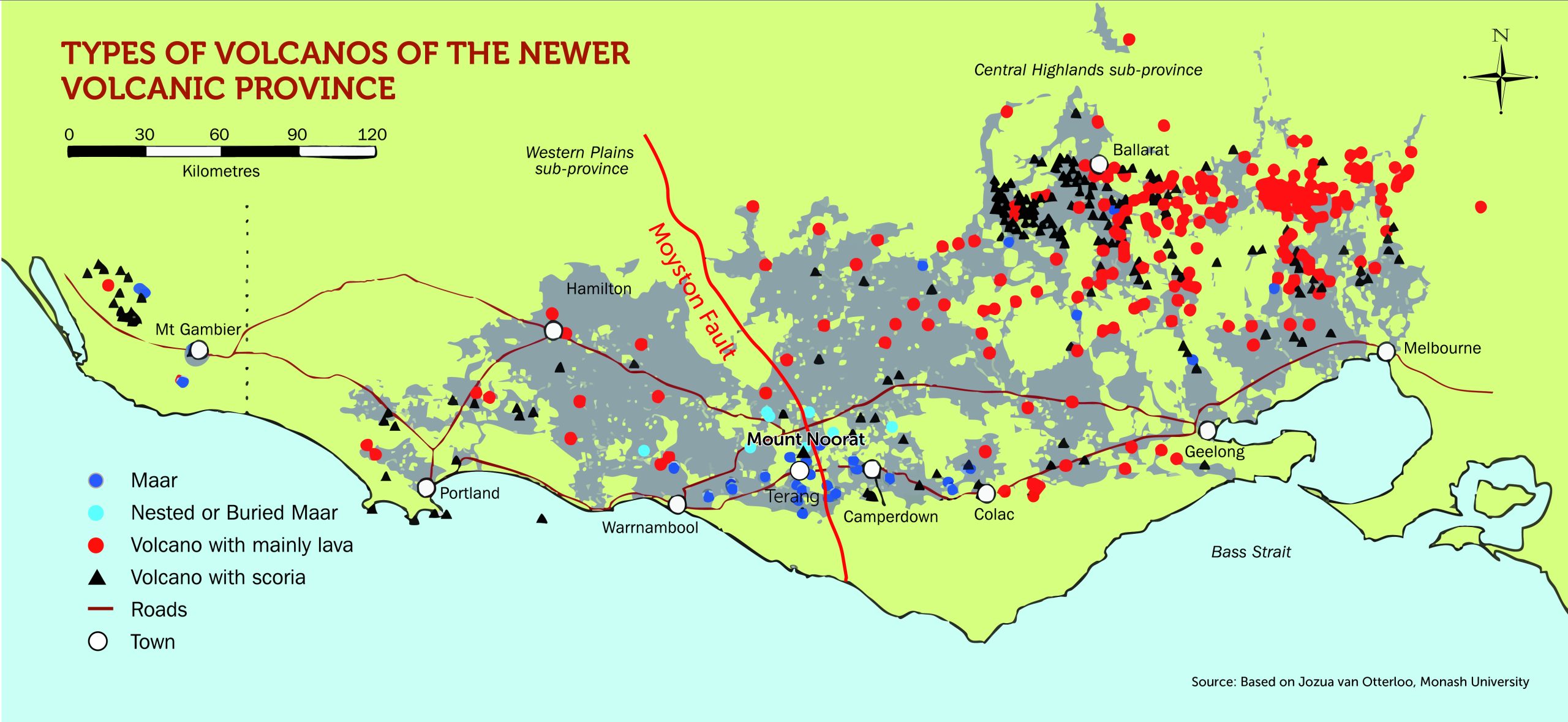

The Newer Volcanics Province contains about forty maar-tuff ring complexes, including some of the largest in the world, such as Tower Hill and Lake Purrumbete. These are mostly in the southern part of the VVP between Colac and Warrnambool.

STAGE 2 - SCORIA CONES

The most prominent features of Noorat’s landscape today belong to the scoria cone stage, which formed as the second stage of the Noorat volcanic complex. These features include the dominant Noorat scoria cone and crater as well other low mounds and small craters.

As the initial eruptions continued, but the amount of groundwater available to interact with the magma diminished, the eruptions became less violent. However, sufficient gas was present to fragment the magma and project it into the atmosphere. This was most likely quite a spectacular process - called fire fountaining.

The magma fragments cooled rapidly in the air and fell back to earth as solid fragments (tephra) which built up around the vent. Due to the gaseous characteristics of the Mt Noorat eruptions the tephra often has numerous gas bubbles (vesicles) trapped in it. This type of volcanic rock with numerous gas bubbles entrapped is called Scoria.

When scoria forms the bulk of a volcanic cone, it is called a scoria cone; hence Mt Noorat is called a scoria cone.

Tephra is divided into three classes based on size: ash (<2 mm), lapilli (2-64 mm) and blocks and bombs (>64 mm). At Mt Noorat, it appears the tephra is quite coarse, being dominated by coarse lapilli sized fragments of scoria as well as volcanic blocks and bombs.

The bombs are of particular fascination. They show streamlined shapes, which indicates that they were semi-molten when they were thrown into the air, spun through the air as they cooled, and then landed adjacent to the crater. The largest bombs are 2 m in diameter! A walk around the crater rim will present opportunities to see some of these large bombs.

Whatever their size, the fragments have the composition of basalt, which is typically a dark, very finely crystalline volcanic rock.

Some tephra fragments however contain smaller, often green fragments surrounded by dark basalt. A useful name for fragments of green or other colours is xenolith, meaning “foreign rock”. Xenoliths are of special interest because they are samples of the mantle or lower crust far below and have been intensively studied to improve our understanding of those deep regions. Green xenoliths are dominated by the mineral, olivine.

Imagine Mt Noorat forming as a continuous jet of magma and gas shot into the air from a hole in the ground (a vent) which is now marked by a spectacular crater. The character of the eruptive products that form Mt Noorat can be seen on the soil surface, in engineering scrapes and in one major outcrop high on the NE wall of the crater.

As the amount of gas continued to decline so did the vigour of the eruptions.

While the crater is steep everywhere, a rock exposure (spatter rampart) on the north-eastern wall of the crater is almost vertical. This was created by the welding (fusing together to form solid rock) of the volcanic fragments which were particularly hot and molten when they fell back to earth. The formation of the spatter rampart was transitional to the end of Stage 2.

STAGE 3 - LAVA FLOWS

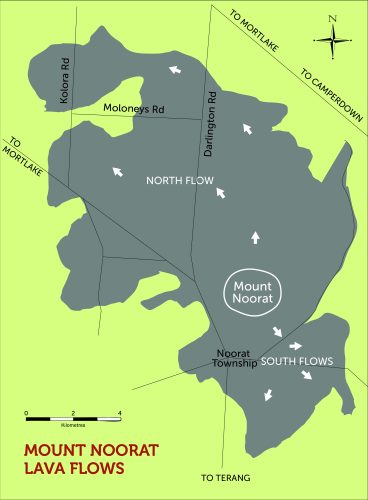

The youngest component of the Noorat volcanic complex is a group of lava flows on the north, south and eastern sides of Mt Noorat.

Quiet eruption of lavas from the ring fractures below the complex led to the formation of several lava flows, some largely featureless but the northern one developing a stony-rise topography in places. (See map)

The largest is the northern flow, which extends about 7 km north of Mt Noorat and covers about 30 km2.It displays a variety of surficial features. Close to the eruption point on the northern side of Mt Noorat is a field of stony rises, which is a very rough volcanic landscape marked by the presence of pressure mounds (tumuli), depressions and lava channels with paired levee banks. Further north, such landforms disappear, and the lava surface becomes smooth.

Mt Noorat is a particularly attractive example of the hundreds of eruption points that exist in the Newer Volcanics Province of south-eastern Australia. It is on the site of three different types of eruptions, each of which resulted in a different suite of landforms and volcanic products. Mt Noorat’s well-formed cone and crater are the most eye-catching of these, but understanding the full history of the Noorat volcanic complex requires inquiry into the maars, tuff rings, lava flows and dykes that are also present. Overall, the Noorat complex covers 42 km2, much of which is low-relief lava plain.

Volcanic Legacy

The subsequent 100,000 years has resulted in the formation of a soil profile on the volcanic products. Minerals and glass in the volcanic materials have reacted and interacted with the atmosphere and plants and have been altered to form clays and other new minerals. The result has been the formation of rich volcanic soils.

It was the basis for a wide variety of indigenous flora and fauna …almost all of which are now are gone.

Home to the Kirrae Wurrung people for millennia.

In more recent times, a place for farming and quarrying.

Mt Noorat continues to be a place of interest and study amongst volcanologists and geologists.

A place for recreation, tourism and learning for everyone.

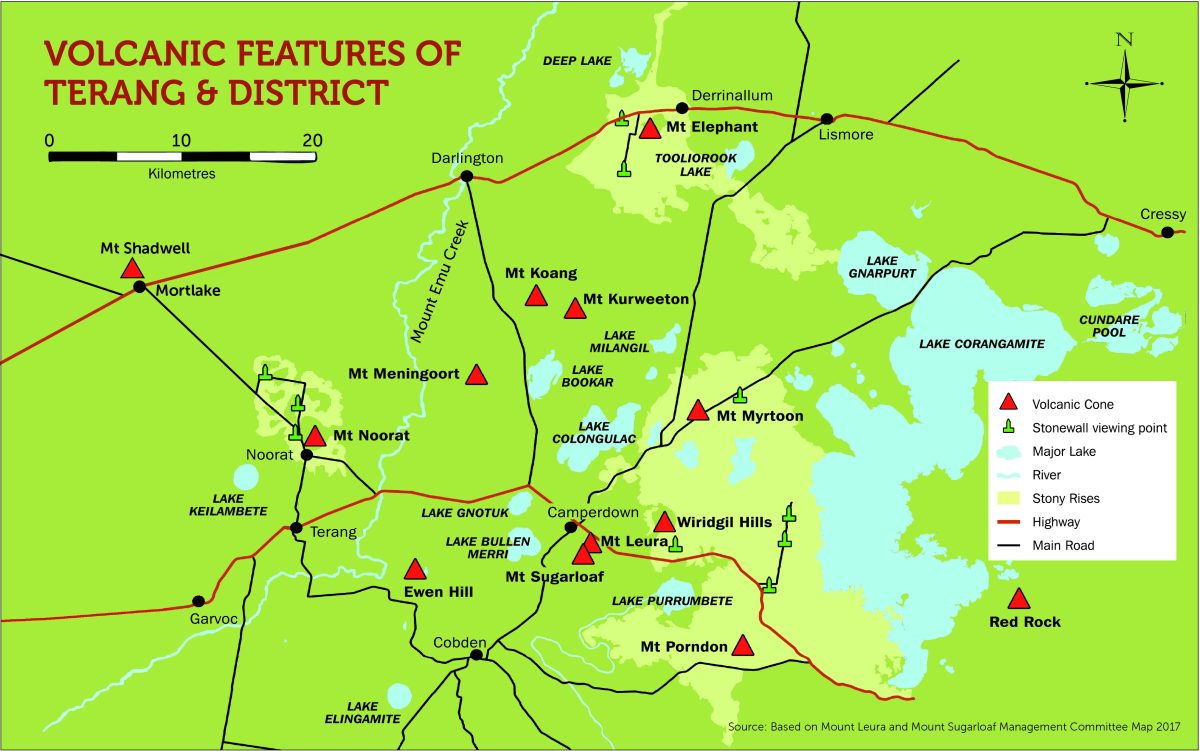

Mt Noorat is one of many fascinating volcanic landforms and features of our small part of SW Victoria – as shown in the map below:

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Stephen Carey,

School of Engineering, Information Technology and Physical Sciences, Federation University.

The content above is based almost entirely on Stephen’s document he provided to the Mount Noorat Management Committee in 2021 as part of his brief to research the geology of Mt Noorat for the Committee.

Please click on the link to access a copy of Stephen Carey’s full document, ‘Geology and Geomorphology of the Mount Noorat Volcanic Complex’